| Example |

|---|

S2 = { div2(X) | lt4(Z) | ~odd(Z)

~div2(Y) | even(Y)

~even(s(s(Z))) | ~odd(Z)

~lt4(s(s(s(s(U)))))

odd(s(s(s(s(s(s(s(zero)))))))) }

|

This refinement is refutation complete for Horn clauses, but refutation incomplete for non-Horn clauses, although it does sometimes work for non-Horn clauses. A special case of refutation completeness for non-Horn sets is when the non-Horn set is renamable (by consistently swapping signs for some predicates) to a Horn set.

| Example, S2 renames (flipping lt4) to: |

|---|

S2' = { div2(X) | ~lt4(Z) | ~odd(Z)

~div2(Y) | even(Y)

~even(s(s(Z))) | ~odd(Z)

lt4(s(s(s(s(U)))))

odd(s(s(s(s(s(s(s(zero)))))))) }

|

| Example |

|---|

S2 = { ~p(X) | q(X) | ~r(X),

p(a) | p(b),

~q(Y),

r(a),

r(b) }

|

and any path from a leaf non-unit clause towards the root of the tree :

On such a path, it is necessary that at some stage a unit clause or the empty clause must be reached. In the path indicated in the above tree, the first unit clause reached is ~p(a). Starting again towards the root, again a unit or empty clause must be reached, in this case immediately at p(b). So, a unit resolution proof can be broken down into chunks that end with the production of a unit resolvant or the empty clause. In the above proof tree the chunks are :

Unit resulting (UR) resolution builds refutations by creating such chunks. The unit clauses used are called electrons, and the single non-unit clause the nucleus. The intermediate clauses of each chunk are not kept, but are instead regenerated, e.g., ~p(X) | r(X) has to be generated twice. UR resolution can be implemented directly in the ANL algorithm by initially placing all unit input clauses into ToBeUsed and the non-units into CanBeUsed. The unit resolvants are placed in ToBeUsed. The first electron of each chunk is the ChosenClause. The nucleus and other electrons are taken from CanBeUsed. There is some loss of effectiveness of subsumption, due to intermediate clauses not being used in subsumption (smart solution - if an intermediate clause subsumes another, replace the other clause with the intermediate clause).

| Example |

|---|

S2 = { div2(X) | lt4(Z) | ~odd(Z)

~div2(Y) | even(Y)

~even(s(s(Z))) | ~odd(Z)

~lt4(s(s(s(s(U)))))

odd(s(s(s(s(s(s(s(zero)))))))) }

|

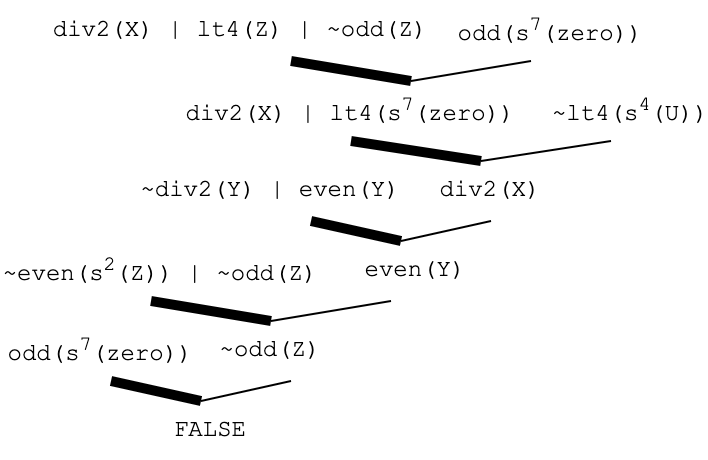

Here is the proof tree ...

| Example |

|---|

S2 = { ~p(X) | q(X) | ~r(X),

p(a) | p(b),

~q(Y),

r(a),

r(b) }

HB = { p(a), p(b), q(a), q(b), r(a), r(b) }

O = p(a) > p(b) > q(a) > q(b) > r(a) > r(b)

|

Notice all the possible resolutions that are prevented by the ordering strategy.

In the above example, the resolved upon literals all were or became ground in unification. Thus it was always possible to check that the largest Herbrand based literal was used in each clause. However, this is not always the case. If variables are unified then it is not necessarily known that the literal is the largest Herbrand based in the clause. An analogous problem arises if the ordering is not total, i.e., some pairs of terms or literals are not comparable.

| Example |

|---|

S1 = { p(b) | r(Y) | p(Y),

~p(S) | p(b),

~p(b),

~r(a),

~r(c) }

HB = { p(a), p(b), p(c), r(a), r(b), r(c) }

O = p(a) > p(b) > p(c) > r(a) > r(b) > r(c)

|

Here is the proof tree for the first part of a derivation.

If ~r(a) is used to complete the refutation, the proof does not conform to the ordering restriction at the first resolution. Here's the proof tree with variables instantiated up the tree. Note that p(a) is the largest atom in p(b) | r(a) | p(a)

However, until the time of that last inference, it is not known at the time what value the variable X will instantiated to. Similarly, if ~r(c) is used in the last step instead of ~r(a) then it will still not conform. A proof tree that conforms is:

The solution is to do restrospective checks (which is very expensive), or do ordering on only the predicate symbols (which is easy but less restrictive), or use a ground completable ordering (which is harder but more restrictive). Read on ...

| Example |

|---|

S2 = { ~p(X) | q(X) | r(X),

p(a) | p(b),

~q(Y),

~r(a),

~r(b) }

O = p/1 > q/1 > r/1

|

Ordering is a refutation complete strategy

| Proof |

|---|

| To be filled in. Based on working up the failure tree. |

A reduction ordering is ...

| Example |

|---|

F = { joe/1, kevin/1, turkey/0, chicken/0 }

if joe(X) > kevin(X) then joe(turkey) > kevin(turkey) if turkey > chicken then joe(turkey) > joe(chicken) there is no infinite sequence joe(turkey) > joe(chicken) > kevin(turkey) > kevin(chicken) > turkey > chicken > ???? |

An ordering R is ground complete if for all pairs of ground terms or atoms (elements of the Herbrand Universe or Herbrand Base) HUT1 and HUT2, one of the following holds ...

An (simplification) ordering O is ground completable if there exists a ground complete reduction ordering R such that O is a subset of R, i.e., the pairs of terms ordered by O are ordered the same by R, and R may order some more pairs of terms that are not ordered by O.

Knuth-Bendix Ordering is an example of a simplification ordering. It is not ground complete, but is ground completable. KBO uses a precedence ordering ρ and a weighting function ω.

and

| Example | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

S = { even(sum(two_squared,b)),

two_squared = four,

~zero(X) | difference(four,X) = sum(four,X),

zero(b),

~even(difference(two_squared,b)) }

ρ : even > zero > = > sum > difference > four > two_squared > b

|

KBO can be used to identify literals in a clause that are known to be smaller than another, clause according to their atoms. An optional additional rule is that if a positive and negative literal are identical then the positive one is smaller. If there is equality in the problem and the system uses built-in equality reasoning (see later), then the comparison by arguments must not be used when comparing two equality literals (or must take into account the symmetry of the arguments). This is discussed in the section on equality. The KBO weighting function ω can also be used for clause selection in the ANL loop.

| Example, using KBO for everything | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

S10 = { ~p(a) [4]

~q(W) | s(W) [6]

~s(X) | p(a) [7] (Subsumed by ~s(X))

~r(Y) | s(Y) [6]

p(Z) | q(Z) | r(Z) } [9]

|

| Example |

|---|

S1 = { p(b)1 | r(Y)2 | p(Y)3,

~p(S)4 | p(b)5,

~p(b)6,

~r(a)7,

~r(c)8 }

|

Notice the marked reduction of the search space.

| Example |

|---|

S2 = { ~p(X)1 | q(X)2 | r(X)3,

p(a)4 | p(b)5,

~q(Y)6,

~r(a)7,

~r(b)8 }

|

| Example |

|---|

S = { bf(a),

~bg(a),

~bf(X) | bh(X),

~bj(X) | ~bi(X) | bf(X),

~bh(X) | bg(X) | ~bi(Y) | ~bh(Y),

bj(b),

bi(b) }

|

Lock resolution is a refutation complete strategy

| Proof |

|---|

| To be filled in. |

S2 = { ~p(X) | q(X) | r(X),

p(a) | p(b),

~q(Y),

~r(a),

~r(b) }

S11 = { p(X) | ~p(f(X))

~p(a)

p(S) | q(S) | r(S)

~q(T) | p(a)

~r(T) | p(a) }

S2 = { ~p(X) | q(X) | r(X),

p(a) | p(b),

~q(Y),

~r(a),

~r(b) }

S11 = { p(X) | ~p(f(X))

~p(a)

p(S) | q(S) | r(S)

~q(T) | p(a)

~r(T) | p(a) }

p(f(X),X) p(f(X),Y) p(a,X) q(f(X),X) q(f(a),X) p(f(a),a) p(X,Y) q(X,Y) q(X,X) p(a,a)

S = { t(a)

~t(Z) | q(Z) | r(Z)

~q(W) | ~p(W)

p(X) | ~t(a)

~r(Y) | ~p(Y) }

(Disclaimer - I have not worked out the answer to this exercise, so it may go weird on you.

Bug reports are welcome :-)